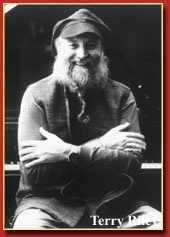

Biography

Der kalifornische Komponist und Pianist Terry Riley begründete mit revolutionär neuen Strukturen in der Klassischen Musik das, was heute als Minimal Music bekannt ist. Sich verknüpfende repetitive Muster beeinflussten prominente Komponisten wie Steve Reich, Philip Glass und John Adams, aber auch Rockgruppen wie The Who, Soft Machine und Tangerine Dream.

Terry Rileys hypnotische, vielschichtige, polymetrische, grossorchestrierte und östlich beeinflusste Improvisationen bereiteten den Weg für die 10 Jahre später entstandene populäre „New Age“ Bewegung.

Ensembles wie Kronos Quartet, Rova Saxophone Quartet, Array Music, Zeitgeist, Steven Scotts Bowed Piano Ensemble, California E.A.R. Unit, David Tanenbaum, Abel Steinberg-Winant Trio, Tracy Silverman, Werner Bartschi & Amati String Quartet führten seine Werke auf, darunter auch zahlreiche Auftragskompositionen.

Terry Riley arbeitete auch jahrelang mit dem Improvisationsensemble Khayal zusammen und gründete mit ihm in den letzten Jahren die Theatergruppe „The Travelling Avant-Garde“, um seine Kammeroper ,,The Saint Adolf Ring‘ aufzuführen.

Seine Solokonzerte sind improvisatorische AusfIüge, ausgehend von den Kompositionen der letzten 30 Jahre – Ende offen….

Die amerikanische „Musiklegende“ am Piano – seine piano solo performances sind in den USA inzwischen zu Kultveranstaltungen geworden….nur noch vergleichbar mit den Klavierkonzerten von Keith Jarrett…New York Times

Ich bin wie ein Archäologe, der die grösste Befriedigung aus Entdeckungen zieht‘, sagt Terry Riley über sich selbst.

Anfang der 6Oer Jahre brach der amerikanische Komponist und Tasteninstrumentalist zu einer Entdeckungsreise auf, die ihn in musikalisches Neuland führte und zum Erfinder der Minimalmusik werden liess.

Die neue Stilrichtung vollzog einen radikalen Bruch mit der Vergangenheit. Riley schwor den Glaubenssätzen der Neuen-Musik-Avantgarde ab, die damals entweder dem Zufallsprinzip oder hochkomplexen mathematischen Kompositionsverfahren huldigte und steckte dafür den Grundsatz der Wiederholung kleiner Motive ins Zentrum seines Schaffens. Seine Stücke steuerten weder auf einen Höhepunkt zu noch arbeit-eten sie nach dem Muster von Spannung und Entspannung. Vielmehr floss Rileys Musik intentionslos dahin. Oder, wie es ein Kritiker ausdruckte: Minimalmusik ist, wie wenn man an einem Sommertag auf einer Wiese in der Sonne liegt und den Himmel betrachtet: Er verändert sich laufend und bleibt doch immer gleich.

Der entscheidende Anstoss zur Entstehung der Minimalmusik kam aus der bildenden Kunst. Maler wie Mark Rothko oder Ad Reinhardt hatten in den 5Oer Jahren die bildliche Aussage ihrer Gemälde so weit zurückgenommen, dass nur die mono-chrome Leinwand übrigblieb. Riley, der damals gerade sein Musikstudium abgeschlo-ssen hatte, blieb davon nicht unberührt und wandte das Reduktionsverfahren auf seine Musik an.

Seine 1964 uraufgeführte Komposition .,ln C“ wurde zur Initialzündung. Der kleine Aufführungssaal im Tape Music Centre von San Francisco war mit etwa 150 Zuhörern gut gefüllt, die auf KIappstühlen um die Musiker herum sassen. Eine gewissen Spannung lag in der Luff, weil das Gerücht die Runde gemacht hatte, dass hier etwas Aussergewöhnliches passieren würde. Dann gingen die Lichter aus, zwei Projektoren warfen farbige Lichtkegel und abstrakte Muster an die Wände und die vierzehn Musiker setzten ein.

,,Die erste Aufführung von ,In C‘ war überwältigend,“ erinnert sich Riley heute. Es war ein exklusives Ensemble mit Steve Reich, Jon Hassell und Pauline Oliveros. Und im Publikum sass jeder, der in San Francisco irgend etwas mit Kunst, Literatur und Musik zu tun hatte.“

So vehement die Minimalmusik Konventionen der klassischen Musik ablehnte. so prägend war der Einfluss femöstlicher Traditionen. Das Prinzip der langen Dauer, hypnotische Wiederholungen und statische Klänge wurden zum Stilmerkmal.

Neben Kalifomien mit seinem asiatischen Flair war San Francisco von besonderer Bedeutung für die ,,Geburt“ des neuen Stils. In der Hochburg der Hippies gab es eine breite Gegenkultur, die mit neuen Lebensformen, Drogen, freier Liebe und fern-östlichen Religionen experimentierte, was für künstlerische Neuerungen eine stimulierende Atmosphäre schuf.

Die Minimalisten waren Teil der Subkultur, mit engen Verbindungen zur alternativen Rockszene. Mit der Musikkommune Grateful Dead teilte man nicht nur Ideale, sondem auch das Zimmer Steve Reich und Phil Lesh (Bassist vor Grateful Dead) wohnten eine Zeitlang zusammen.

Der fernöstliche Emfluss wurde so stark, dass sich Riley Anfang der 7Oer Jahre vom eigentlichen Musikleben zuruckzog, um sich ganz dem Studium der indischen Musik zu widmen. Er wurde Schüler von Pandit Pran Nath, einem Meistersänger der klassisch indischen Musik.

Erst Ende der 7Oer Jahre kehrte Terry Riley ins eigentliche Musikleben zurück. Am Mills College in Oakland/California, wo er eine Zeitlang unterrichtet hatte, war er David Harrington, dem ersten Geiger des Kronos Quartetts begegnet, der Riley für eine Kooperation gewann. Aus der Zusammenarbeit gingen neun Streichquartette hervor, von denen , Salome Dances for Peace“ das umfangreichste ist. Ein Mammut-werk von über zwei Stunden Dauer, an dem Riley zwei volle Jahre gearbeitet hatte u. das ihn schlagartig wieder ins Zentrum der Aufmerksamkeit rückte.

lnzwischen ist die Minimalmusik von einer Rebellion zu einer etablierten Strömung im modernen Musikbetrieb geworden. Philipp Glass, Michael Nyman u. John Adams haben dem Stil zum kommerziellen Durchbruch verholfen. Selbst in der Popmusik haben Rileys Ideen ein breites Echo gefunden, so in den Sounds von Brian Eno, Robert Fripp/ King Crimson oder Tangerine Dream. Und die jungen Soundbastler der aktuellen ,,Ambient-Szene“ kann man mit emigem Recht als die Enkel von Terry Riley betrachten.

Discography

‚In C‘ with Members of the Center of the Creative and Performing Arts at SUNY Buffalo

CBS 1968

‚Cadenza on the Hight Plain‘ Kronos Quartet

Gramavision 1985

‚The Padova Concert‘ solo piano

Amiata Records 1992

‚Chanting the Liqht of Forsiqh‘ Rova Saxophone Quartet

New Albion 1994

‚In C – The 25th Anniversary Concert‘ live at Life on the Water Theatre in San Francisco with members of Rova, Kronos

New Albion 1995

‚No Man’s Land / Conversation with the Sirocco‘ with Krishna Bhatt, Zakir Hussein

Plainis Phare 1996

‚The Lisabon Concert‘ solo piano

New Albion 1996

Reviews

Im Strom der Klänge

‚Ich bin wie ein Archäologe, der die grösste Befriedigung aus Entdeckungen zieht‘, sagt Terry Riley über sich selbst.

Anfang der 6Oer Jahre brach der amerikanische Komponist und Tasteninstrumentalist zu einer Entdeckungsreise auf, die ihn in musikalisches Neuland führte und zum Erfinder der Minimalmusik werden liess.

Die neue Stilrichtung vollzog einen radikalen Bruch mit der Vergangenheit. Riley schwor den Glaubenssätzen der Neuen-Musik-Avantgarde ab, die damals entweder dem Zufallsprinzip oder hochkomplexen mathematischen Kompositionsverfahren huldigte und steckte dafür den Grundsatz der Wiederholung kleiner Motive ins Zentrum seines Schaffens. Seine Stücke steuerten weder auf einen Höhepunkt zu noch arbeiteten sie nach dem Muster von Spannung und Entspannung. Vielmehr floss Rileys Musik intentionslos dahin. Oder, wie es ein Kritiker ausdruckte: Minimalmusik ist, wie wenn man an einem Sommertag auf einer Wiese in der Sonne liegt und den Himmel betrachtet: er verändert sich laufend und bleibt doch immer gleich.

Der entscheidende Anstoss zur Entstehung der Minimalmusik kam aus der bildenden Kunst. Maler wie Mark Rothko oder Ad Reinhardt hatten in den 5Oer Jahren die bildliche Aussage ihrer Gemälde so weit zurückgenommen, dass nur die monochrome Leinwand übrigblieb. Riley, der damals gerade sein Musikstudium abgeschlossen hatte, blieb davon nicht unberührt und wandte das Reduktionsverfahren auf seine Musik an.

Seine 1964 uraufgeführte Komposition .,ln C“ wurde zur Initialzündung. Der kleine Aufführungssaal im Tape Music Centre von San Francisco war mit etwa 150 Zuhörern gut gefüllt, die auf KIappstühlen um die Musiker herum sassen. Eine gewissen Spannung lag in der Luft, weil das Gerücht die Runde gemacht hatte, dass hier etwas Aussergewöhnliches passieren würde. Dann gingen die Lichter aus, zwei Projektoren warfen farbige Lichtkegel und abstrakte Muster an die Wände und die vierzehn Musiker setzten ein.

‚Die erste Aufführung von ,In C‘ war überwältigend,‘ erinnert sich Riley heute. Es war ein exklusives Ensemble mit Steve Reich, Jon Hassell und Pauline Oliveros. Und im Publikum sass jeder, der in San Francisco irgend etwas mit Kunst, Literatur und Musik zu tun hatte.“

So vehement die Minimalmusik Konventionen der klassischen Musik ablehnte. so prägend war der Einfluss femöstlicher Traditionen. Das Prinzip der langen Dauer, hypnotische Wiederholungen und statische Klänge wurden zum Stilmerkmal.

Neben Kalifomien mit seinem asiatischen Flair war San Francisco von besonderer Bedeutung für die ,,Geburt“ des neuen Stils. In der Hochburg der Hippies gab es eine breite Gegenkultur, die mit neuen Lebensformen, Drogen, freier Liebe und fern-östlichen Religionen experimentierte, was für künstlerische Neuerungen eine stimulierende Atmosphäre schuf.

Die Minimalisten waren Teil der Subkultur, mit engen Verbindungen zur alternativen Rockszene. Mit der Musikkommune Grateful Dead teilte man nicht nur Ideale, sondem auch das Zimmer Steve Reich und Phil Lesh (Bassist vor Grateful Dead) wohnten eine Zeitlang zusammen.

Der fernöstliche Einfluss wurde so stark, dass sich Riley Anfang der 7Oer Jahre vom eigentlichen Musikleben zuruckzog, um sich ganz dem Studium der indischen Musik zu widmen. Er wurde Schüler von Pandit Pran Nath, einem Meistersänger der klassisch indischen Musik.

Erst Ende der 7Oer Jahre kehrte Terry Riley ins eigentliche Musikleben zurück. Am Mills College in Oakland/California, wo er eine Zeitlang unterrichtet hatte, war er David Harrington, dem ersten Geiger des Kronos Quartetts begegnet, der Riley für eine Kooperation gewann. Aus der Zusammenarbeit gingen neun Streichquartette hervor, von denen ‚Salome Dances for Peace“ das umfangreichste ist. Ein Mammutwerk von über zwei Stunden Dauer, an dem Riley zwei volle Jahre gearbeitet hatte u. das ihn schlagartig wieder ins Zentrum der Aufmerksamkeit rückte.

lnzwischen ist die Minimalmusik von einer Rebellion zu einer etablierten Strömung im modernen Musikbetrieb geworden. Philipp Glass, Michael Nyman und John Adams haben dem Stil zum kommerziellen Durchbruch verholfen. Selbst in der Popmusik haben Rileys Ideen ein breites Echo gefunden, so in den Sounds von Brian Eno, Robert Fripp / King Crimson oder Tangerine Dream. Und die jungen Soundbastler der aktuellen ‚Ambient-Szene‘ kann man mit einigem Recht als die Enkel von Terry Riley betrachten.

‚Live in Lisboa‘ – the Composer at Play

Altough he’s written for a large number of ensembles including Kronos String Quartet, Orchestra, Rova Saxophone quartet, and chorus, Terry Riley’s primary instrument has always been the piano. Since the age of eight, when he began piano lessons on a Colfax, California farm where his grand mother got her eggs and chickens, Riley has composed and improvised at the piano at every major stage in his career. It makes sense, then, that for his sixtieth birthday tour he chose a solo piano program drawing together a range of music spanning the last several decades, including pieces derived from such large-scale works as Salome Dances for Peace, A Rainbow in Curved Air, and The Saint Adolf Ring.

Riley’s travels across the musical map find a home base in these solo piano pieces. This album distills a career of experience as a barroom piano player, student of Indian and Western classical traditions, founder of minimalism, advocate of just intonation, composer / improviser, and master of many keyboards. Interestingly, this synthesis takes place in each piece. Ideas shift and trasform organically and seamlessly, one melting into another by imperceptible increments, until you realize the music has metamorphosed radically into something very different It’s astonishing that such a diverse range of elements can coalesce, across the entire keyboard, from a visceral rumbling bass to ecstatic figurations in the highest register.

This live recording is a document of the Final concert in Riley’s sixtieth birthday European tour, on July16, 1995 for the Festival dos Capuchos at the Teatro Sao Luis in Lisbon, Portugal. The listener can imagine Riley at the Hamburg Steinway, on stage in the centuries-old gilded rococo theater with red velvet seats and ornate decor.

On this magical night in the magical city of Lisbon a kind of retrospective of my work unfolded and I felt the spirit play through me in a way that gave feelings of rare and deep emotion. Here and there are exhilarating moments in which are framed split second decisions, which opened up entirely new avenues of musical direction and exploration. And finally it must be said that, without an audience, none of this could be brought into existence in the same way. The shared attention to the sound current helps to channel the spontaneity and inspiration that makes this experience one of life’s most sacred and privileged moments.

Listen, for instance, to the stylistic scope of „Island of Never Anger“, which begins with a sort of Chopin-etude-meets-habanera, and leads into jazzy counterpoint. The right hand riff becomes a left hand backdrop for a brilliant display of ornamentation. And the bluesy chromatic progressions of „Negro Hall“ merge into a groove of motoric minimalist patterns.

The Lisbon piano is in equal temperament, while Riley’s preference is for the more colorful intervallic relationships of just intonation. However, he manages to reveal colors and characters not usually associated with this most commonly used tuning. In „Negro Hall“, for example, a major tenth (held by the sostenuto pedal) repeats in the bass, and overlayed harmonies create a kind of frictive resonance that reminds us of the beating in just intonation.

As in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Riley’s compounding of intervals coaxes out a whole spectrum o chromatic hues. What emerges most in this recording is the exuberance and pleasure of a lifetime of diverse musical activity. What might seem like polar opposites find common ground in Riley’s performances. These pieces are full of playfulness, and also packed with complexity. He dazzles us with virtuosic passagework, and then shows us the simple pleasures of a series of major sixths. Within that simplicity is sixty years of composition, of travels around the globe, of an extraordinary range of knowledge and experience brought back once again to the piano.

Specials

THE RING OF SAINT ADOLPH

Kammeroper u.a. mit :

TERRY RILEY – Piano / Vocal

TRACY SILVERMAN – Violine / Vocal

JEAN JEANRENAUD – Cello

It is based on the works of Adolph Wulfi. He was a Swiss peasant who was born around 1864 and had a terrible childhood. He was neglected, his father was an alcoholic, he was a ward of the state, his mother died when he was very young and he was sent out as a hireling around the farms in Switzerland. He wandered around Switzerland like this for about thirty years as a laborer and stuff. Around the age of thirty he was caught molesting a young child in a cradle. He actually had been involved in other cases before too and had been put in jail because of one of them.

But when he was thirty, they had diagnosed him as schizophrenic and was put in a mental institution, and spent the next thirty-five years almost in solitary confinement. In this mental institution and after about five years he started drawing and he had the most incredible ability to draw and conceptualize art considering he had never been to art school and knew nothing about what was happening. He was a very visionary artist. His art is always about vision of something. One of his hallucinations or he said people would visit him and tell him what to draw and then they would argue about what he should draw and then he would argue with them. But he turned out thirty thousand or something drawings and stories about travels through space, travels throughout the earth, places he had never been too, because he spent his entire life in a mental institution. He described New York and Canada in great detail and gave them really fantastic names, with great plays on words.

When I first discovered his art, it was like a revelation. I had never heard of him, I couldn’t believe it, he was such a great artist and nobody never heard about him. But now outsider art is beginning to get known. After I saw Wulfi’s work, I wanted to do some piece on him because he really set off something in me when I saw it, I felt like I had to deal with it. First I was going to make it purely a musical piece and then it looked like it had to be a theater piece because a lot of Wulfie’s writings are so imaginative and his words are so imaginative, I thought they had to be spoken in each piece so we sort of developed this woven fabric of music and narrative dialog. We would mix it all together with video images and slides. Then the actors were speaking and telling stories.

Mit dieser Kammeroper nahm Terry Riley das vorweg, was Robert Wilson & Phil Glass mit „Monsters of Grace“ in München (Okt. 98) präsentierten. Phil Glass betrachtet diese Form der „Oper“, d.h. das Zusammenspiel von Bild, Video, Computer, Musik als die „Oper der Zukunft“ (Interview – BR/TV vom 20.10.98).

Terry Riley setzt in seiner Kammeroper Musik, Schauspieler, Tänzerin, Pantomime, Bilder, Computer, Video, Licht und verschiedene Sounds ein. Er arbeitet auch mit der Schizophrenensprache Glosserlallia und den halluzinativen Zeichnungen/Visionen mit kryptischen Musiknotationen des Adolf Wulfi, dessen Lebensgeschichte Grundlage der Kammeroper ist.

Besetzung:

* Piano/ Vocal – TERRY RILEY

* Violine/ Vocal – TRACY SILVERMAN (Turtle Island)

* Cello – JEAN JEANRENAUD (Kronos)

* Schauspieler / Actor

* Tänzerin / Sängerin / Pantomime

* Light Designer

* Stage Designer

* Video/ Dia Techniker

* Sound Ingenieur

An interview with Q

Ambient music has been around for centuries, take the call of Whales, or the drone of a dijereedoo, it’s only recently in the 70’s that ‚ambient‘ has been used as a term to classify music. Brian Eno was, in the main, responsible for this, with his concept of threshold hearing. Eno was very influenced by a generation of composers whose work came to prominence in the 60’s – the minimalists, central of whom is the california based composer Terry Riley.

Q : Basically tell us who you are.

Terry Riley : Well I guess my music came to prominence around one piece called ‚In C‘ which I wrote in 1964 at that time it was called ‚The Global Villages for Symphonic Pieces‘, because it was a piece built out of 53 simple patterns and the structure was new to music at that time. No one had done anything like this before were you just had a piece built all out of patterns and the first concerts of ‚In C‘ were kind of big communal events where a lot of people would come out and sometimes listen or dance to the music because the music would get quite ecstatic with all these repeated patterns. Although repetition is a major force in music it was never used in this way before. So, essentially my contribution was to introduce repetition into Western music as the main ingredient without any melody over it, without anything just repeated patterns, musical patterns. In the nut shell that was my own introduction into the world of western music

Q : What were you doing before ‚In C‘ came out?

T.R : I was working with Anna Halprins Dance Company. I was working with tape loops, sort of primitive technology. This was in the late 50’s early 60’s. I was using tape loops for dancers and dance production. I had very funky primitive equipment, in fact technology wasn’t very good no matter how much money you had. Everything was mono. Using these machines I would take tapes and run them into my yard and around a wine bottle back into my room and I would get a really long loop and then I would cut the tape into all different sizes and I would just run them out into the yard and I would record onto one machine just sound on sound. I would build up this kind of unintelligible layer, almost like some of these things you have been playing. It was like primitive sampling. I would take things like Junior Walker and his All Stars and would cut it up and play it backwards and stuff like that. Out of doing all that experimentation with sound I decided I wanted to do it with live musicians. To take repetition, take music fragments and make it live. Musicians would be able to play it and create this kind of abstract fabric of sound.

Q : What kind of instruments were you playing at this time?

T.R : I was mainly playing piano.

Q : Your first record was called „Reed Stream“

T.R : That was on an old organ harmonium that I had a vacuum cleaner motor blower blowing into the ballast’s. The vacuum cleaner motor kind of had a drone, so I played along with that. Talking about the all night concerts, I did some of the first all night concerts back in the 60’s with this little harmonium, and I also had saxophone taped delays. I was asked to do the first all night concerts. I did a solo all night concert which started at 10:00 at night and ended at sunrise. People brought their whole families and they had their sleeping bags and hammocks. It was in one of the big rooms in art college. It started out a career for me doing all night concerts which I did for a couple of years.

Q : How did you prepare for these all night concerts?

T.R : I really didn’t have a plan, I just went in and started playing. One of my specialties was to be able to play for a really long time without stopping and I would play these repeated patterns for hours and hours and I wouldn’t seem to get tired. I guess I have a lot of energy. Throughout the evening I would be recording these long saxophone delays and about four hours into the concert, if I wanted to take a break I would just play back the saxophone. And a lot of people didn’t even wake up to know the difference because a lot of people just slept all night.

Q : I heard in a lot of your concerts you used lights shows?

T.R : I traveled with an artist, Bob Benson, he used have strobe lights and we built these mylar screens. He was a painter essentially. His paintings were stretch color fabric on canvas, then he started stretching reflective mylar. Sometimes I would have troops of girl gymnasts doing cartwheels during the night shows just as a passing. Then we would have these mylar things so the audience would see themselves and they would see me. They looked quite distorted because the mylar, as it bends, distorts the reflection kind of like the mirrors at the circus.

Q : When people talk about minimalist music the lineage seems to go (according to media) La monte Young, you, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and I was wondering when you first came across La monte what went on between you. I know you’ve played concerts together, I always got the impression that the influence went both ways.

T.R : Well, he was certainly a big influence on me when I met him, he was the freakiest guy I have ever met in my life. I met him when I went to school in Berkeley. He was in one of my classes and we struck it off as close friends from the beginning. I think he was much more sophisticated musician. He had lived in Los Angeles and been a jazz musician, and I was coming out of the sticks of Northern California and I hadn’t heard nearly as much music as he had. He has a superb conceptual sense about music, I think his sense about music is what spawned minimalist music, even though he didn’t do it the way Glass and Reich, who where more inspired by me because of the repetition. La monte’s idea was just to have this one big form that were just long tones, I think that was the real essential heart of minimalist music.

Q : How were those pieces live?

T.R : He wrote one for me, that I’ve never performed yet, but maybe I will someday. It was where I was supposed to push a grand piano into a wall and keep pushing until the wall fell down.

Q : Could you talk a little about your encounters and development of your relationship with Pandit Pran Nath?

T.R : I met him through La Monte Young. La Monte had brought him over in 1970 and La Monte had been one of the first people in America to recognize how great he was. He had been underground figure performing in India on the radio. He wasn’t considered by the Indian public at large as one of the great superstars, like Ravi Shankar. But in effect, he had all this great knowledge of Indian classical music and really performed it in a true sense. I had been interested in Indian music and I actually started studying Tableaus before I met him. I was sort of going in that direction because my own music was very similar to Indian music. When I met him [Guruji] he said ‚You must become my student.‘ So I said, ‚OK.‘ I cried the first time I heard him sing. He hit some bell in me that had never resonated before. It was so moving I wanted to go back to India with him right away and start studying with him. I had already done Rainbow in Curved Air and had a big record on CBS. I was launched to have a long career and then I just dropped out and went to India. So I just went to India to study with Pandit, and he said no you have to do your own music too.

Q : Tell us about the music-theater piece you are working on now?

T.R : It is based on the works of Adolph Wulfi. He was a Swiss peasant who was born around 1864 and had a terrible childhood. He was neglected, his father was an alcoholic, he was a ward of the state, his mother died when he was very young and he was sent out as a hireling around the farms in Switzerland. He wandered around Switzerland like this for about thirty years as a laborer and stuff. Around the age of thirty he was caught molesting a young child in a cradle. He actually had been involved in other cases before too and had been put in jail because of one of them. But when he was thirty, they had diagnosed him as schizophrenic and was put in a mental institution, and spent the next thirty-five years almost in solitary confinement. In this mental institution and after about five years he started drawing and he had the most incredible ability to draw and conceptualize art considering he had never been to art school and knew nothing about what was happening. He was a very visionary artist. His art is always about vision of something. One of his hallucinations or he said people would visit him and tell him what to draw and then they would argue about what he should draw and then he would argue with them. But he turned out thirty thousand or something drawings and stories about travels through space, travels throughout the earth, places he had never been too, because he spent his entire life in a mental institution. He described New York and Canada in great detail and gave them really fantastic names, with great plays on words. When I first discovered his art, it was like a revelation. I had never heard of him, I couldn’t believe it, he was such a great artist and nobody never heard about him. But now outsider art is beginning to get known. After I saw Wulfi’s work, I wanted to do some piece on him because he really set off something in me when I saw it, I felt like I had to deal with it. First I was going to make it purely a musical piece and then it looked like it had to be a theater piece because a lot of Wulfie’s writings are so imaginative and his words are so imaginative, I thought they had to be spoken in each piece so we sort of developed this woven fabric of music and narrative dialog. We would mix it all together with video images and slides. Then the actors were speaking and telling stories.

Q : Are the words sung or spoken?

T.R : Some of them are spoken and I’ve written some songs for the scripts. Some of them are in German and others are in English. Some of the ones in German are just based on sounds which are really interesting, there even not sounds common to Germany. They are sounds Wulfli had made up. You know there is this language schizophrenics call

Glosserlallia which is a secret language that only they understand.

Q : So schizophrenics can talk to each other in this language?

T.R : No, they can only talk to themselves. Most of them have many people dwelling within themselves, and they all speak Glosserlallia. They probably each have their own version of the language. I found that to be fascinating though. The big part of art and music is imagination. The thing that grips us is imagination of the artist, and schizophrenics are some of the most imaginative people. It makes you wonder what is the real heart of art and music. What are we really trying to get at? I think what happens to them, their ordinary filters for reality somehow open up. They experience things we can only experience in very altered states, but they experience this all the time.

Q : Did you see music in Wulfli’s pictures, and did you develop themes to certain pictures?

T.R : I did. A lot of his drawings also have music notations in them. He developed his own system of music notation and no one has ever been able to decipher it. It is very cryptic and enigmatic notation. When I saw a lot of those I really thought it sounded like great music just looking at it on the page although I would never know how to decipher it, so I decided to compose music just in a spirit of what he is doing. I wanted to write music that was influenced by my studying his drawings. So I spent a lot time this summer just gazing at the drawings. The music has come out kind of interesting, it almost sounds like music that could have been composed in the 30’s and 40’s around the time he lived. I haven’t really wanted to do anything modern. It’s general substance is older sounding.

Q : What are your thoughts on where the world is going?

T.R : It is important that we are coming up on the millennium because what I am experiencing, just being one person out of billions, is the feeling of acceleration. I experience this through my contact with other people. Everyone seems to be in a kind of accelerated time mode that is beyond their own control. Acceleration is finite, I think according to some laws of physics. It seems like we are moving towards something, some kind of point and it is probably going to be an important point in our development or dissolution. That is what everybody seems to be thinking. We are either going to dissolve as a human race or we are going to break through into a new understanding of what it is to be a human being.

Q : So what part is music going to take in this transformation?

T.R : This morning I was practicing raga, and at one point I was singing a long tone and I became very peaceful and still. I thought this is really the highest point of music for me is to become in a place where there is no desire, no craving, wanting to do anything else, just to be in a state of being to the highest point. Then you get a little meditated, you get to a place that is really still and it is the best place you have ever been and yet there is nothing there. For me, that is what music is. It is a spiritual art. It is a form to that place. There are many ways to do that, many kind of ways to get there. Music can also be a sensual pleasure, like eating food or sex. But its highest vibration for me is that point of taking us to a real understanding of something in our nature which we can very rarely get at. It is a spiritual state of oneness. For me, it is the reason for doing music because you are always trying to get there, but we live in this big cloud of illusions, so we sometimes go about it in the wrong way. We think music as being as a highly skilled activity, virtuosity. To me it’s important that you acheive the state. Listening to music is as high as singing or playing it. If a great singer is singing and you think gee I would like to sing like that, you are being foolish because you are listening to the thing you really want anyway, so why think you want to do it. It is the thing, the thing itself that is really important. Although I have a personal greed about playing music, I really enjoy the tactile thing of playing an instrument, but I’m coming from back in 1935, when that was the way you made music, there is no other way to do it, so I have a lifelong habit of doing music this way. But if I was 20 years old today, I might not have that orientation, I would probably be out sampling music like everybody else.

The interview was conducted at Shri Moonshine ranch October 1992 by Gamall and Ammon Haggerty. ©qaswa 1995.

Music

T. Riley & T. Silverman – Moonshine

JOHN MCLAUGHLIN world premiere and Euro Tour of „Europe“ for Jazz guitar and Orchestra – „Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie“ known as „Thieves and Poets“

CHICK COREA for ever

Paquito D´RIVERA

Dee Dee BRIDGEWATER a tribute to Billy Holiday

IMANI the outstanding Afro-American Wind Quintet

TANGO FIRST CENTURY a delightful combination of exciting music & dance

Aniello DESIDERIO performing John McLaughlins Guitar Concerto „Europa-Thieves & Poets

Quartet Furioso „Vivaldi & Piazzolla

Alvaro PIERRI „The fine Art of Guitar playing

CLARINET SUMMIT Sabine MEYER meets Paquito D´RIVERA

Tracy SILVERMAN “ the greatest living exponent of the electric violin – BBC“

The legendary Terry RILEY